It’s hard not to admire Reece Harding, who died in Syria fighting for the Kurdish peshmerga against IS. His sense of social justice, idealism and internationalism led him to take up arms against an organisation he seemingly believed lived up to Tony Abbott’s characterisation as a ‘death cult’.

His father, Keith Harding, told the ABC:

With all the information that’s spread about on the internet with people beheading people, killing children, raping and beating women, I think it really did get to him in the end […] He felt that he wanted to do the right thing and try and stop it in his small way that he could […] I’m sure that’s the driving force of him going to do this.

The Islamic State hasn’t made any effort to hide its brutality; on the contrary, it’s promoted it and used it as a perverted recruiting tool. But the Federal Government has also used it to stoke fear within Australia, play-up the risk of terrorism at home, dismantle democratic freedoms and the rule of law and boost its own approval rating.

The media saturation, the constant ‘death cult’ references and the battle between the two major parties over who can better protect Australians has meant politicians have benefitted from the characterisation of IS as a force more violent and ruthless than the world has ever seen.

IS has a special status, partly because of their online propaganda, but also because politicians have afforded it to them. There’s hardly been a week in the past year that the PM hasn’t made a direct or indirect reference to the rape and torture of the Yazidis. But when was the last time he mentioned the schoolgirls kidnapped by Boko Haram?

Reece Harding was simply answering the prime minister’s increasingly nationalistic and jingoistic calls to ‘degrade and ultimately destroy’ the ‘Islamist death cult’.

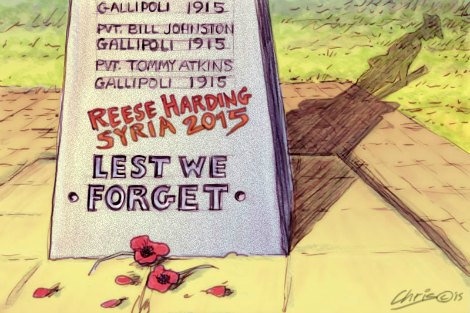

The government has warned Australians against travelling to the Middle East to fight on any side. But these calls are drowned out by decades of contradictory rhetoric that has seen the Anzac legend (or myth) placed at the very fore of Australian history and culture. It’s become Australia’s great foundation story, filling the void of the revolution she never had and obscuring the mass murder of the Aboriginal people.

‘Anzac values’ and ‘Australian values’ have become synonyms embodying ideas of larrikinism, mateship and disdain for authority. After more than a decade of John Howard promoting Gallipoli as Australia’s most important military engagement – despite it being a resounding failure – and few politicians or pundits challenging him since, these qualities are more venerated now than they’ve ever been.

The centenary celebration of the Gallipoli landing was a reminder of just how prominent a place the conception of ‘Anzac’ has in contemporary Australian society. All the pomp and circumstance cost upwards of $30 million – an expensive exercise to celebrate an event that has become dangerously divorced from any historical reality.

But who could deny the streak of larrikinism and disdain for authority in Reece Harding’s decision to disregard Australian law and travel to join the war in Syria? There’s also photos of him, published on The Lions of Rojava Facebook page, arm in arm with his fellow soldiers – his mates.

It may seem paradoxical to be compelled by Australian/Anzac values to take up arms and join an organisation other the ADF, but changes in the way wars are now fought means that this logic is perfectly in keeping with military developments.

The rise of private military contractors – mercenaries, if you will – during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars has shattered the idea that armies are an exclusively national force. In an essay for The Monthly, James Brown writes that at its peak, ‘the conflict in Iraq employed over 20,000 armed private security contractors.’ ‘Australian contractors’, he explains, ‘are prolific in the private security world, alongside Americans, Britons and South Africans.’

The Australian public has, therefore, had over a decade to get used to the idea that their fellow citizens are fighting in wars that their government supports, but for security firms that aren’t subjected to any executive oversight. These mercenaries do the jobs that national armies either can’t, won’t or don’t want to do.

The parallels between these contractors and the Kurdish forces are not insignificant. The Federal Government agrees that airstrikes alone will not be sufficient to defeat IS. Troops on the ground need to take the fight to IS too, and the Kurds are just one of the West’s proxy fighting forces.

Reece Harding understood that Australia’s commitment to fighting IS is mostly tokenistic and that her impact will be largely inconsequential. In a video released after his death, he says: ‘I volunteered to join the YPG in the fight against Daesh. I believe the Western world is not doing enough to help.’

He wanted to help. He gave up his life to fight an organisation – an ‘Islamist death cult’ – all Australians are being told to fear. Spurred on by a sense of internationalism, he did something, one suspects, many politicians – if they didn’t have to contend with the political backlash – would like to commit more Australians to do. If there’s anyone who embodies that great Australian construct – the ‘Anzac spirit’ – it’s Reece Harding. We shouldn’t lose sight of that.

(This was originally published in Eureka Street on 12 July, 2015.)