The Battle of Stalingrad – although the word ‘battle’ doesn’t begin to fully capture its carnage and destruction – was one of those reminders from the twentieth century of the true destructive power of totalitarian regimes. The willingness of Hitler to sacrifice his troops rather than surrender and Stalin’s insouciance about the suffering of the civilians of the city that bore his name gave rise to one of the bloodiest battles of all time. While the number of casualties will probably never be known, one gets a sense of the scale of slaughter when one considers that prior to the German attack Stalingrad is thought to have had 850,000 residents, when a census was taken just five years later in 1945 only 1,500 remained.

It also marked the point at which many of the German officers begun to realize that their increasingly delusional Fuehrer was in decline and, with that, so too were the hopes of their country. The Germans were forced to relinquish their control of the Eastern Front and it preempted their capitulation in the West. For the Soviet Union, it was their greatest victory of the Second World War.

Stalin’s triumph, despite the waste of human lives, was also celebrated with great gusto by the Allied democracies. They were fully aware that an Axis victory at Stalingrad would probably have spelt defeat for them too.

Yet Churchill and Roosevelt would’ve undoubtedly adopted a different strategy to their Bolshevik alley; one that tried to minimize the civilian casualties and not relied so heavily on the wholesale slaughter of their troops. And even if they were willing to follow Stalin’s line, it’s unlikely they’d have maintained popular support to remain at the helm of their respective governments.

Here in lies the reason the United States – with the best equipped and most advanced military in the world – can no longer lay claim to being to world’s leading military power. By almost every measure the United States possess far greater military capabilities than China, but she simply couldn’t sustain as many casualties and remain committed to the war effort as long as the rising superpower.

Democracies are imperfect, but they do ensure the rights of their citizens are better protected than any other system of government. (In light of the Snowdon revelations there’s cause to reexamine this idea, but I’d maintain that basic premise. There are, after all, plenty of examples of nominal democracies acting in flagrantly undemocratic ways.) The checks and balances in place in democratic societies are often criticized for increasing inefficiency and, in times of war, the deployment of troops to be used as cannon fodder simply doesn’t come to pass in modern democracies.

One can argue about the details, but this remains at the core of why the United States couldn’t ‘win’ in Vietnam, Afghanistan or Iraq.

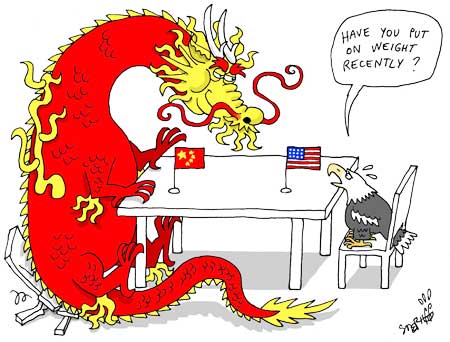

This should not be misconstrued as a call for less democracy, nor do I think there’s great cause for concern. As Chinese President Xi Jinping said last week at the opening of the annual talks between the world’s two largest economies, confrontation between the two nations would be a disaster. It really is difficult to underestimate just how disastrous such a war would be; the global economy would collapse as two nuclear powers battled it out.

Nonetheless, it’s worth thinking about what could provide the tinder for confrontation between the U.S. and China. The obvious choice is one of the many territorial disputes China has in the South and East China Seas, with the U.S. rushing in to support her allies in the region.

But I think the recent tension is more about Chinese posturing for internal political gains: Exerting her power and influence in the region, while ensuring the people remain united behind the Communist Party. What better way to do this than by manufacturing a common enemy?

Whereas the United States is war-weary, China is in a state of expectance (I certainly wouldn’t say readiness though). The ‘common enemy tactic’ is hardly a Chinese invention – remember George Bush’s declaration that you’re either with ‘us’ or with the terrorists – but it serves a different ideological purpose for the Communist Party than it does other governments.

In China the bellicose, anti-imperialist chauvinism is part of what legitimizes the Communist Party’s rule. Unlike the United States, modern China was born out of a humiliating defeat in the Opium Wars. It wasn’t until the Communist Party, led by the young revolutionary Mao Zedong, rose to power and evicted the Japanese that China begun to be restored to its past glory (or at least this is what’s believed in China). I’ve often thought that this is the reason why Mao, despite being responsible for the deaths of tens of millions of people, is still almost universally revered in China, whereas Deng Xiaoping, the architect of China’s economic rise, is not a comparable figure in modern Chinese history.

In many ways the Communist Party’s rule is more reliant now than ever before on its ability to present itself as the protector of this tradition. The decision to embrace capitalism has left the CCP with a substantial ideological void and if it were seen to capitulate to the imperialists it’s hard to see what it would be left with to justify its rule.

In the United States, a land of free and fair elections (and where the debacle that was the 2000 presidential election can take place and be resolved peacefully), the government’s legitimacy is won or lost at the ballot box. And there can’t be many faster ways to lose popular support than having young men and women returning from distant lands in coffins, draped in the ‘Stars and Stripes.’

But with the neo-conservatives out of the White House, the United State’s foreign policy – which can essentially be characterized as an on-going effort to remain the world’s hegemonic power – has become less overtly militaristic. There are, of course, other elements by which power can be measured – it’s hard to see China eclipsing America’s cultural influence anytime soon – and as the Middle Kingdom continues to rise one would be misguided in thinking the world is moving towards another Cold War-style era.

The interconnectedness of markets now means that even the threat of war between China and the United States would have dire consequences for national economies around the world. It’s a risk that a developing China and a declining U.S. cannot afford; nevertheless, military might will become an increasingly important measure by which to compare the two nations.