The vitriol with which much of the liberal mainstream media responded to Tony Abbott’s Margaret Thatcher memorial speech last month confirmed what many rightwingers have been claiming: that the scorn towards the former PM was a result of his conservative social values and that the problem was not his policies, but rather, his inability to sell them.

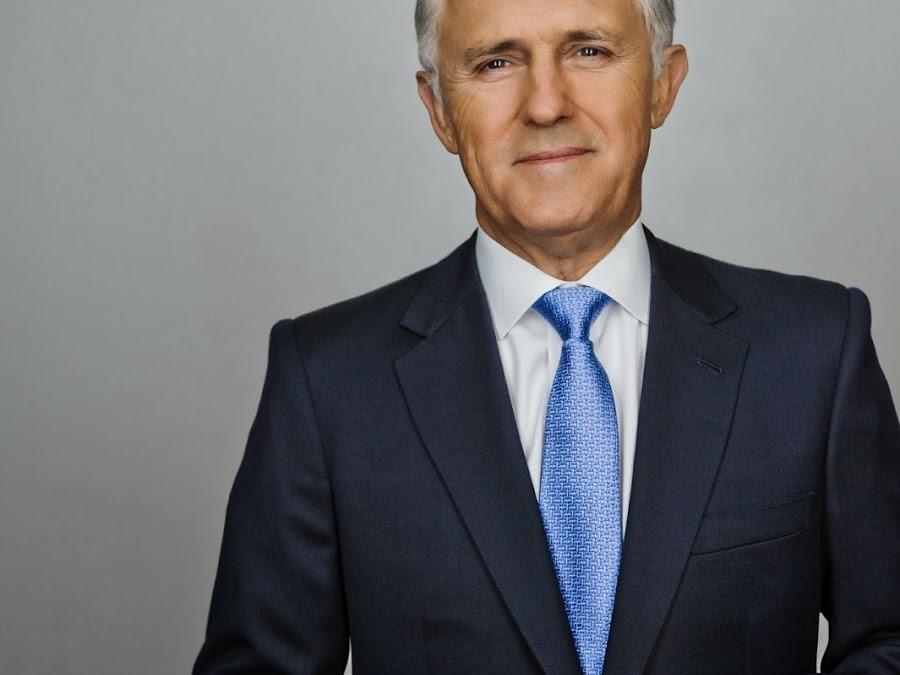

After all, as Abbott was lecturing European Tories on the virtues of his ‘turn back the boats’ policy, current Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull — the man currently implementing that very policy — was enjoying unrivalled popularity.

Their competing fortunes and popularity couldn’t be more divergent, yet they both agree that the leadership switch hasn’t ushered in any significant policy changes.

Fresh from his first round of international summits as prime minister, the polls suggest Turnbull is (for the moment, at least) untouchable.

Labor’s efforts to paint him as ‘out of touch’ didn’t get much traction, but they’ll likely try again before the next election.

Significantly, the reaction to Senator Sam Dastyari’s decision to use parliamentary privilege to query Turnbull’s investments in that infamous tax haven, the Cayman Islands, says much about Australia’s political discourse. Fairfax slammed the move, calling it ‘lame’ and claiming Labor has flicked the switch on ‘class warfare.’ The media class almost universally agreed the ‘tactic’ had failed. But by whose measure? Well, their own, of course.

All the ‘system is broken’ punditry that had become an obsession for the mainstream media in the Rudd-Gillard-Rudd-Abbott days is apparently obsolete now that Australia has a prime minister who talks and dreams big. (Remember when Tom Elliott declared that ‘democracy isn’t working right now. It’s time we temporarily suspended the democratic process and installed a benign dictatorship to make tough but necessary decisions’? Ah, good times.)

As communicators, Turnbull and Abbott are poles apart. His refusal to start ‘spinning your way into somebody you are not’ is refreshing because there’s a growing frustration with the current crop of wooden politicians who are so scared of saying something stupid that they say nothing at all.

But for Turnbull to decry the professional wordsmiths and manipulators is somewhat ironic. After all, he should be their poster boy. Having done nothing other than change the messaging, he’s turned the Coalition’s fortunes around.

It’s not that I want to underplay the significance of the leadership change. Indeed, Turnbull looked instantly comfortable among the world’s leaders last week, in stark contrast to Abbott, whose cringe-worthy performance at the G20 had many Australians squirming with embarrassment.

And, of course, eventually a Turnbull-led government will introduce new policies that will be divergent from those of the Abbott government. But the leadership change is a band-aid solution that has been greeted by broad sections of the electorate as somehow revolutionary.

Turnbull’s ascension has in fact done nothing to address some of the most significant challenges facing Australia today: rising job insecurity, an anemic economy, a growing gulf between the richest and poorest, unaffordable housing (particularly in Melbourne and Sydney), inhumane border protection policies, climate change, a political class more divorced than ever before from the everyday struggles of the majority of Australians and a fragmenting society, to name but a few.

Yet you wouldn’t know this from reading the mainstream media. How did it come to be this way?

The armies of ‘communication specialists’ are now so immersed in the political system that it’s almost never acknowledged that spin — which is essentially massaging or distorting the facts to manufacture a more attractive product — is undemocratic. The policies or ideas have become less important than the packaging and salesmanship.

But the spin-doctors aren’t exclusively to blame. If they could be banished from the political system, the media would still remain a tool of the powerful, with dissident and unpopular views rarely given a voice.

The relationship between the mainstream media and politicians and their minders is symbiotic. They rely on each other for information, access and exposure. It’s a club and, like any club, joining is conditional upon certain values: namely, being socially liberal with a belief in the almost divine power of the free market. For those who sign up and sing from this song sheet, affluence will be assured.

These are the people that frame the national debate and, inevitably, manage public opinion. In Turnbull they seem to have found a kindred spirit.

Thus, it’s become acceptable for pundits to declare ‘class warfare’ when questions are raised about Turnbull’s investments. But, as Ben Eltham pointed out, the fact that the PM ‘is a multimillionaire, with a household wealth in excess of $100 million’ is ‘by any normal standard of democratic discourse, a legitimate topic of debate’.

To date, the most striking achievement of the Malcolm Turnbull confidence trick is that he’s rewarded for his apparent progressivism, even when he speaks explicitly against it. The media barely batted an eyelid when he said: ‘Coal is a very important part, a very large part, the largest single part of the global energy mix and likely to remain that way for a very long time.’

He even suggested that if Australia stopped all coal exports, global emissions might actually increase because Australia’s coal is cleaner than that of other countries. So much for his lead-by-example approach from yesteryear.

While delivered with less machismo than Abbott’s ‘coal is good for humanity’ comments, they’re not all that different. Yet they went uncriticised by the media.

The same is true when he extols the virtues of the government’s direct action policy, despite being a long advocate of an emissions trading scheme. Perhaps it’s because the media know he’s just reading from a script that he doesn’t believe in. It’s just spin to placate the right within his party. Yet somehow he’s managed to retain the image of himself as some kind of conviction politician.

This current wave of Turnbullmania is a symptom of a shallowness of the mainstream political discourse in Australia, where a leadership change can be seen as a kind of solution, while the fundamental problems with the system can be, once again, wilfully ignored. At least with Abbott in charge those problems were laid bare for all to see.

(This was originally published in Eureka Street on 24th November, 2015.)