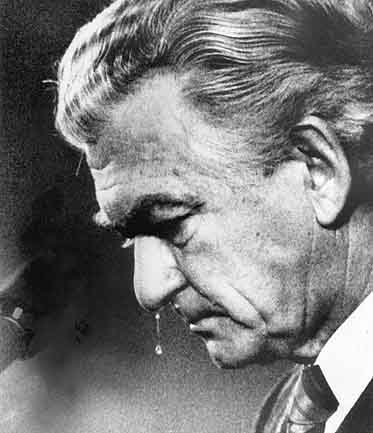

On 4 June, twenty-five years ago, the Chinese government turned the guns of the People’s Liberation Army on their own people as they protested peacefully in the streets of Beijing. It was a response so gross and ruthless that it left the rest of the world dumbstruck. In Australia, it precipitated an elegiac moment in our history; the last time a leader of one of the major parities responded to the plight of asylum seekers humanly. Prime Minister Bob Hawke sobbed as he promised Chinese students studying in Australia that if they didn’t want to return home they wouldn’t have to: Australia would offer them shelter.

He did this instinctively; there was no government policy on how to respond to the Chinese government’s slaughter of its own people. In fact, Hawke’s offer conflicted with the Labor Party’s immigration policy at the time. It was a human response to a human tragedy.

How things have changed: now, to draw attention to the plight of asylum seekers or to try and elicit public sympathy for them invites catcalls from the other side of the House, with the risk of being labelled ‘‘soft’’ on border protection. Refugees are not seen for what the majority of them are: people fleeing persecution or death. They’re all slapped with blanket terms like ‘‘economic refugees’’, or ‘‘queue jumpers’’, or ‘‘potential terrorists’’ who are depicted as trying to subvert Australian values.

The often unstated importance of Australian values in this debate is best understood not by examining who we subject to the oppressive processing guidelines, but rather, who we exempt. Take the case of the Pakistani-born cricketer Fawad Ahmed, who had his application fast-tracked after lobbying from Cricket Australia who wanted to select him for their tour of India.

Documents have subsequently come to light under Freedom of Information that confirm his case was ‘‘borderline’’ and that he received special treatment. But in a country where more people care about the football results than the election results, sporting prowess buys one considerable social capital. This is the hypocrisy of the system; politicians perpetuate the message that all asylum seekers pose a threat to the safety and prosperity of ‘‘ordinary Australians’’, but their willingness to subvert the normal process and make exceptions in dealing with Mr. Ahmed’s application just go to show that these are nothing more than manufactured, populist slurs.

It also illustrates other failings of the political establishment and the public; namely, that attitudes towards refugees are inconsistent and irrational. For all of Prime Minister John Howard’s deceitfulness and open hostility towards refugees, it was the once-moist Hawke who coined the phrase ‘‘queue jumpers’’ in 1992 to describe Cambodians fleeing the Khmer Rouge (a regime that killed between 2 and 3 million people). How he could react, in one instance, with great sensitivity and, in another, with such callousness is difficult to reconcile. I suspect it has to do with the power of the footage from the 1989 massacre, of which the iconic footage of the man standing in front a row of tanks is the best remembered. It’s one thing to read or hear about people being killed, but quite another to see it.

This same principle was at play during he Vietnam War. Often referred to as the first television war, it drove many Vietnamese people to risk their lives on rickety junks in the hope that Australia would offer them protection. And we did; we welcomed about 137,000 Vietnamese refugees (most selected from resettlement camps) and gave them a chance at a better life. It was an era when both major parties refused to play politics with lives, and the overwhelming emotion garnered for them by Malcolm Fraser and Gough Whitlam was compassion.

We’ve come full circle: refugees are no longer treated as people, but as political instruments. No longer are the policies of the major parties dictated by values, or principles, or an altruistic desire to help create a better society; increasingly, policy is determined by the results of focus groups and polling. (An indication of just how much this has degraded the Australian political system is best expressed by Mark Latham in his Diaries; lunching with Mark Arbib following the 2004 election, Arbib gives his some feedback on the results from the focus groups: ‘You need to find new issues, like attacking land rights, get stuck into all the politically correct Aboriginal stuff – punters love it.’)

It’s a despairing irony that both major parties still essentially have a bipartisan position on refugees, but that it’s now built on xenophobia and white Australian nationalism; the very things Fraser and Whitlam – the white Australia policy only recently having been revoked – feared igniting and committed themselves to repressing.

There is, however, an inconsistency with the idea that the televised violence of war somehow conditions a more ruthful society. If that was the case the rise of the Internet may well have coincided with a mass conversion to Gandhism. But the saturation of violence has desensitised us and the people fleeing it now longer win our sympathy.

And recent Australian governments – firstly under Howard, then under Rudd and Gillard, and now under Abbott – have used their disproportionate might in propaganda campaigns to drown any sense of sympathy the public may be inclined to feel for those that risk their lives by fleeing to Australia. It’s no coincidence that refugees are imprisoned in gulags in remote desert regions of Australia and on impoverished Pacific islands, far away from prying public eyes and the media.

Politicians have, time and again, done everything in their power to cast asylum seekers as in some way defective. The Howard government’s treachery in accusing asylum seekers of throwing their children overboard in 2001, when they were actually trying to escape their burning boat, marks a point at which common humanity, honesty and decency became untenable political positions for the major parties: Howard won the election based on a lie and Australia re-elected him in 2004. And Kevin Rudd, a man who once lectured Australia on the need to re-think our attitude to refugees, came up with the most draconian policy of all; a policy that was so ‘good’ (that is to say, a real vote-winner) the Coalition said they’d adopt it too.

But the country’s horrendous refugee policies are a symptom of a much wider trend in Australian politics that threatens to do irreparable damage to Australian society; the willingness of politicians to exploit ugly, populist undercurrents in Australian society to win votes has sent us down a path to which there is seemingly no end in sight.

Howard is often lauded as a brilliant political tactician, but he too often simply resorted to picking Australian cultural and political scabs until they bled – undoing much of the admirable work of previous political leaders on both sides of the divide. He launched the ‘cultural wars’ and promoted Keith Windschuttle’s racist version of Australian history, refused to apologise for the crimes committed by white Australians against Aboriginals and refused to condemn Pauline Hanson hostility towards Asian immigrants.

The Prime Minister’s office may once have carried with it a certain prestige and responsibility to rise above irrational and vicious slurs against minorities, but throughout Howard’s term he used and fed these fears to win support. This is Howard’s legacy.

The Abbott government’s manifestation of this tactic now threatens to do serious damage to Australian-Indonesian relations. His disregard for their sovereignty in his pledge to ‘‘tow back the boats’’ might be seen as a good policy now, but there is now way it can be construed it as good long-term politics.

And a meek and dysfunctional Labor Party, unable to construct a tenable position from Opposition, have stood by and let this happen. Rather than take a principled position and raise the level of the public debate, they’ve kowtowed to Howard’s refugee legacy. Kevin Rudd made one of the most important and memorable speeches in Australian parliamentary history when he apologised to the Stolen Generation, but one cannot help but feel that if he thought this was going to hurt him electorally he wouldn’t have done it. He seems a man driven not by conviction, but by a desire for power. His loyalties are not to his party or his constituents, but to himself. And his betrayal of the ALP and Julie Gillard are his most notable contribution to the public’s disillusionment with Australian politics.

Bob Hawke was by no means perfect, but his tears for the Chinese people in 1989 seem so far removed from the current state of affairs that one feels driven to despair. We’ve moved so far from that moment, we’re so deep in manufactured political filth, that the truth and humanitarianism have been relegated as values to which those in Australian public life should aspire; now, leaders look first at what focus groups think, then they ask: ‘How can we show the punters we think this too?’

(This was originally published on Right Now on 3rd June, 2013)